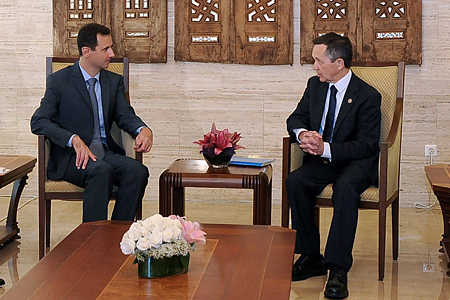

Syria's President Bashar al-Assad meeting with US Congressman Dennis Kucinich in Damascus on June 27, 2011. (Photo: SANA / AFP / Getty Images)

“Visits to Syria have become a vexed issue. Reacting to a visit to Syria by U.S. senators in December, a White House spokesman said that ‘you can take a tough line all you want but the Syrians have already won a PR victory’ simply because visits give ‘legitimacy to a government that undermines the cause of democracy in the region’.”

That is an extract from a 2007 article by Brooks Newmark, a U.S.-born member of the U.K. parliament. He disagreed with the Bush administration’s line on Syria, arguing that “any policy which does not seek to engage all parties with strategic interests in the region will founder before it has even begun.” Fast forward to June 27 2011. The U.S. is under different leadership and so is Britain, with Newmark’s Conservative party leading a coalition. The Arab Spring is redrawing the Middle East in profound, and profoundly unpredictable, ways. And, in a photograph released by the Syrian news agency SANA, Newmark, now a senior government whip, tasked with keeping discipline among his colleagues in parliament, sits in a chair opposite Bashar Assad in Damascus, in what was only the Syrian president’s second meeting with a western lawmaker since he responded to the popular uprising in his country with untrammeled brutality. The first took place one day earlier, with U.S. congressman Dennis Kucinich. During both encounters, Assad “reviewed the recent events taking place in Syria and the advanced steps achieved in the comprehensive reform program,” reported SANA. “For their part Kucinich and Newmark expressed keenness on Syria’s security and stability as an essential pillar in the region.”

That the Syrian government would do its best to spin these visits into exactly the sort of PR victory the White House spokesman feared seems inevitable. Kucinich appears to have gifted the regime ample material, holding a press conference in Damascus covered by the state news agency which attributed the following sentiment to the maverick Democrat:

President Assad is highly loved and appreciated by the Syrians. What I saw in Syria in terms of the open discussion for change demanded by the people and the desire for national dialogue is a very positive thing.

Kucinich rejected this version of events. His words were “mistranslated,” he told the congressional newspaper The Hill in a statement.

Britons still flinch at the 1994 memory of George Galloway, at the time a Labour MP, telling Saddam Hussein “Sir, I salute your courage, your strength, your indefatigability.” (Galloway was captured on film, and was speaking English, but would later claim he was saluting the Iraqi people, not their president.) Critics in Britain were swift to cast Newmark’s appearance in Syria as a Galloway moment. “For [Newmark] to turn up in Damascus when the whole world is very concerned about the repression, the deaths, the arrests, the torture, the disappearances for a nice, friendly cup of tea with the Syrian president is absolutely extraordinary,” said Labour MP and former Foreign Minister Denis MacShane. “Was he representing the government? Was he paid for to go by the government?” MacShane added that although MPs were free to undertake fact-finding trips “you’re less entitled to go when you’re on the government payroll.” Labour’s shadow Foreign Secretary Douglas Alexander wrote to Foreign Secretary William Hague for clarification.

That clarification, in a reply from Hague to Alexander and in conversations with Foreign Office sources, indicates that Newmark’s road to Damascus diverged sharply from Kucinich’s. The two politicians have never met, and their initiatives were unconnected. The State Department has let it be known that Kucinich’s Syrian odyssey involved neither contacts with nor support from U.S. officials. Hague, by contrast, explained that although Newmark’s trip was private—and funded by the MP—he had liaised with the British government before and during the trip. Hague wrote:

Brooks Newmark went to Damascus in a personal capacity having visited President Assad on previous occasions at his own expense, but informed and consulted me in advance. He paid for his visit himself. My officials met with Mr Newmark and they made clear the steps that the U.K. government thinks the Syrian regime should take. He agreed to reflect this in his conversation with President Assad. I believe it is important that we use all means to convey these messages directly to President Assad.

Newmark issued a brief statement: “I was there in a personal capacity and reiterated the government position that there should be an immediate cessation of violence and a clear path to political reform.” He also acknowledged to The Times of London that he understood that his efforts could be co-opted for propaganda. “There is always a risk of that. I want to see an end to violence. We want to see political reform. Anything you can do to stop violence is a good thing. That is all we are doing. To sit back and do nothing is not a solution.”

The MP has traveled extensively in the region over a number of years, focusing on getting to know key players not only in Syria but also Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and most recently Yemen. A report in a British mass market newspaper, the Daily Mail, suggested that behind the scenes, diplomats were less than thrilled by Newmark’s latest exploit. A source in the Foreign Office disagrees, countering:

If individuals have got long-standing relationships they can use to push the message that Assad’s current behavior is outrageous, you can see that as part of the wider international pressure. If we’d been worried that Brooks’ trip could give succor to the regime, we’d have said ‘excuse me, old chap. That’s not helpful’.

Politicians on both sides of the Atlantic are divided on the appropriate response to Syria and its embattled and blood-stained leadership. For now, at least, the U.S. and British governments and broad strains of the international community believe in keeping communications channels open, while imposing sanctions on Assad and his officials. It’s not that there’s much faith in a talking cure—between nations or within Syria, granted a so-called “national dialogue” by Assad that opponents dismiss as a fig leaf to conceal any real moves to reform. It’s that the alternatives are unthinkable.