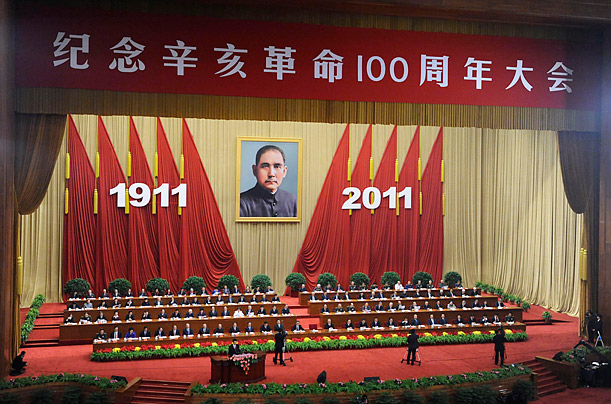

Chinese leaders gather sit beneath a portrait of Sun Yat-sen during an event to mark the 100th anniversary of the Xinhai Revolution. (Photo: Minori Iwasaki / Reuters)

In a country that claims five millennia of history, what’s a mere century? Oct. 10 marks the 100th anniversary of the start of China’s 1911 Xinhai Revolution, which ended 2,000 years of imperial rule. The fall of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) was precipitated by an uprising in the central Chinese city of Wuchang (now part of Wuhan) that eventually led to the formation of a Chinese republic under the tenuous leadership of Sun Yat-sen.

This milestone was celebrated on Sunday by China’s leaders, who gathered under a massive portrait of Sun, the so-called founder of modern China whose republic was soon engulfed by warlord battles, struggles between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Kuomintang, plus the Japanese invasion ahead of World War II. At the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, President Hu Jintao proclaimed that the 1911 event was “a thoroughly modern, national and democratic revolution.” Xinhua, China’s state-run news agency, opined that “the 1911 Revolution not only rid Chinese men of humiliating ponytails and women of the excruciatingly painful foot-binding, but also removed the people’s blind faith in the emperor, as well as fear of foreign powers. The event has since been emancipating people’s minds from thousands of years of oppression and self-enclosure.” (Sunday’s televised ceremony was also notable for the appearance of retired leader Jiang Zemin, Hu’s 85-year-old predecessor, who had missed a July celebration of the Chinese Communist Party’s 90th anniversary, leading to rumors about his illness or even death.)

Imperial China may have officially come to an end in 1911. But is the 62-year-rule of the Chinese Communist Party akin to that of another dynasty whose “mandate of heaven” is being challenged? In his excellent book The Party, Richard McGregor notes that China’s secretive leadership is bereft of ideology but is highly skilled at ensuring its own survival. As a result, the material gains made in the past two decades have turned China into the world’s second-largest economy. But inequality and corruption have proliferated, too. The biggest scandals in China today tend to either involve errant officials—grabbing land from peasants or money from state coffers—or misbehaving fuerdai, the coddled “second-generation rich” who have acted with impunity in traffic accidents and other intersections with society.

And no matter what lip service Hu paid to 1911 as a “democratic revolution,” democracy in China is a dream deferred. The political upheavals in the Middle East and North Africa have spooked China’s leaders, who have unleashed a human-rights crackdown that has netted everyone from artists and dissidents to journalists and lawyers. Even attempts in recent weeks by some independent candidates to run for local People’s Congress positions—something that is allowed by law—have been foiled by official interference.

By contrast, little Taiwan—where the Communists’ enemy, the Kuomintang, fled in 1949—has transformed from an island cowering under martial law to a functioning democracy. Taiwan, which calls itself the Republic of China, has long labeled Oct. 10 “National Day.” For decades, Beijing ignored the date, celebrating Oct 1, when the Communist People’s Republic of China was officially founded, as its “National Day.” But in recent years, Xinhai fervor has been authorized in China, albeit with some constraints. Sunday’s festivities in Beijing were splashed across the front pages of state newspapers, but they paled in comparison to those of Oct 1. A portrait of Sun may have been temporarily placed in Tiananmen Square near the permanent, iconic image of Chairman Mao Zedong, the founder of the People’s Republic; but an opera commemorating Sun was cancelled at the last-minute for “logistical reasons” in Beijing, presumably because his life hardly conformed to an idealized Communist storybook. One of Sun’s political philosophies, for instance, was the Three Principles of the People: nationalism, democracy and the people’s welfare. Sun died in 1925, and his legacy is claimed by both Taipei and Beijing. But the Chinese leadership hasn’t gone out of its way to highlight the democracy part of Sun’s vision.

In his Oct. 9 speech, Hu called for China’s peaceful reunification with Taiwan. A day later, Taiwan’s President Ma Ying-jeou rebuffed any such political union for now and instead urged Beijing to emulate Taiwan’s democratic reforms. But there’s one aspect of the Qing’s dying days that is rarely mentioned in China. The Oct. 10 uprising that signaled the end of China’s imperial tradition happened in part because of ideas that flourished during a reformist era led by certain members of the Qing court. Beijing’s rulers are thought to have learned the same lesson from perestroika and the dissolution of the Soviet Union: reforms can bring troublesome consequences. For the Chinese Communist Party, birthed during political upheaval yet ruling for more than six decades, revolution isn’t quite what it used to be.

(See photographs from the Chinese Communist Party’s 90th birthday.)