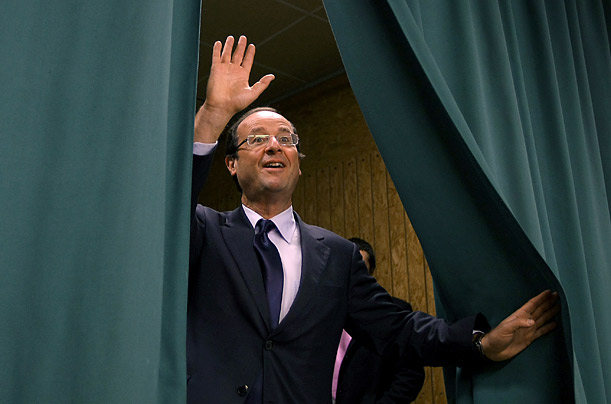

French candidate for the 2011 Socialist party primary elections Francois Hollande waves to supporters, Oct. 16, 2011. (Photo: Bob Edme / AP)

For many people outside France, François Hollande is the man—or the name, at least—they’ve heard will be leading the French left’s effort to oust conservative President Nicolas Sarkozy in general elections next spring. But for many people beyond France, that’s all they know about Hollande–apart perhaps from the supposedly evocative nickname “Monsieur Normal” that the British press invented for the 57 year-old Socialist candidate (and now seems to use with exhausting repetition in the hopes it’ll actually catch on France as well. Good luck with that). So in the interest of moving beyond fabricated monikers for a man French polls currently cast as favorite to become France’s next president, herewith a few salient points on Hollande’s politics, personality, and background.

For starters, Hollande is the anti-Sarkozy in just about every way—both good and bad. Easy going, good natured, accessible and down to earth, Hollande represents a polar opposite to Sarkozy’s swaggering, sharp-tongued, control-obsessed personality that tends to react to any difference of opinion (much less overt opposition) as a personal affront that must be avenged. Often derided as the Bling-Bling President for his unabashed adoration of money and celebrity (something his millionaire heiress wife herself embodies), Sarkozy was probably what the scooter driving, decidedly unflashy Hollande had in mind when he (in)famously opposed the president’s 2007 tax breaks for the wealthy with the explanation, “I don’t like the rich”.

And if the athletic, chic, impeccable Sarkozy has always used his looks and seductive powers for maximum electoral effect, Hollande’s run in the Socialist primaries required him to shed considerable weight, revamp his clothes and eye glasses for a snazzier look, and tether his ever-ready sense of humor for a more serious, stately air. The effort has helped, but Hollande still suffers an image handicap vis-à-vis the polished, commanding, albeit diminutive Sarkozy: try as he might, the Socialist champion has yet to fully shed associations with the cartoon dog Droopy, or the roly-poly, chortling marionette that portrays him on the satiric nightly newscast, les Guignols de l’Info. Fortunately, this isn’t a world where looks matter.

Similarly, their clashing personalities have also produced very different leadership styles. Sarkozy has always been an alpha male preferring to dominate (and even intimidate) his own political family while driving apart all others into distinct camps of friends and foes. Hollande has the reputation for being an even-tempered, low-key assembler. Indeed, in posting his 57% to 43% Socialist Party (PS) primary victory over rival Martine Aubry in Sunday’s final round, Hollande established himself as a consensus candidate that the party’s frequently clashing centrist and leftist factions agreed to get behind. Socialists now hope that unity of cause into 2012 will replace the open divisions that have cost the PS the Elysée since François Mitterrand last claimed it for the left in 1988. Meanwhile, Socialists are counting on Hollande’s positive message and harmonizing tone to strike the same chord after five years of Sarkozy’s more divisive style that Barack Obama’s unifying appeal did in 2008 following the trenchant presidency of George W. Bush.

Yet his very success in assembling divergent camps around a common cause is also already generating concern echoing the complaints that the compromising Obama now face in the U.S.: of a leader confusing strategic concession with political surrender. During his tenure as PS leader from 1997 to 2008—and as an influential heavyweight within the party since then—Hollande placed sufficient premium on bridging differences that some critics say he’s incapable of defending his own positions from challenge. (Worse still, some opponents claim Hollande doesn’t really have any non-negotiable ideals or objectives, and instead swings towards wherever the easiest solution lies.) Those knocks are doubtless over-stated, since no one could rise to such influence in politics without having some sort of consistent line–and a spine to back it up. Yet it remains a concern to some that Hollande’s preference for compromise over clash may leave him unarmed to fend off the frontal personal and policy assaults he’ll come under from entrenched and intransigent foes like Sarkozy and his fellow conservatives—as well as from the harder left.

That, indeed, was the thrust of Aubry’s offensive ahead of Sunday’s run-off vote, when she cast Hollande as a rudderless appeaser and representative of a “soft left” who won’t be able to lure more progressive Green Party and Communist Party voters with his center-leaning line. Whether that’s true or not is yet to be seen: platforms presented by individual candidates in the PS primary were for the most part fairly general and vague, and the real work of crafting a more detailed Socialist presidential program is only just getting under way. For now, Hollande’s main proposals represent a clear turn to the left from Sarkozy’s regime, but hardly the stuff of revolution. He’s spoken of a progressive reform of the income tax regime—with higher rates applied to the wealthy—tighter regulation of banks and financial markets, and increased revenues to fight France’s debt crisis that won’t prohibit measures like creating some 60,000 new teaching jobs to replace those eliminated under Sarkozy.

Not surprisingly, even those initially vague proposals have already led the right to portray Hollande as bent on imposing a catastrophic neo-Marxist regime on France. That began in earnest Tuesday, with Sarkozy’s conservatives staging a two-hour televised broadcast, featuring virtually all members of the government taking turns attacking what they called Hollande’s inapplicable and ruinous Socialist program. The sight of ruling rightists savaging a still nascent Socialist platform while ignoring the rather frustrating—when not counter-productive—results of their own decisions in power has not escaped the sarcastic notice of French pundits.

That musing aside, most French commentators are currently looking at where Hollande has come from to get a better idea of where he may go from here. Born in the Norman city Rouen to a middle class (and politically heterogeneous) family in 1954, Hollande navigated the circuit of prestigious schools that have long produced France’s political, administrative, and business elite—including the iconic Ecole Nationale d’Administration. It was there Hollande met a fellow leftist whose steely demeanor and intellectual rigidity led him to call her “Miss Ice Cube”—an initial perception that didn’t prevent Hollande and 2007 Socialist Party presidential candidate Ségolène Royal from working together in various political roles (including, at one point, advisors in François Mitterrand’s Elysée). Hollande and Royal eventually formed a couple (though never married), and had three children together. They finally announced the end of their union after Royal’s resounding presidential defeat, though the move came long after the troubled relationship had become little more than a façade kept going for appearances.

In hindsight, the breakup was almost certainly hastened by tensions within the PS, and Hollande and Royal’s own intersecting Elysée ambitions. Despite Socialist traditions of the party leader almost inevitably being selected as presidential candidate (though not without often bitter opposition), Hollande respected his previous pledges to hold a primary ahead of the 2007 elections. In doing so, he doubtless imagined that as head of the PS he was also likely to secure its candidacy–primary or not. Instead, Hollande quickly found himself forced to sit out the contest as his increasingly estranged partner Royal took a big, early lead over all other rivals, and coasted from there victory. Not before, however, the PS battle took some bitter, ugly turns. The possibility of it also assuming the form of domestic warfare was apparently too grim for Hollande to risk by entering it himelf—especially given the odds he’d lose to his children’s mother if he did so.

It was doubtless the residual frustration of the missed 2006 primary that led Hollande to enter this year’s edition both early and with great determination. That earned him the ire of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, who was favored to win the PS candidacy and the Elysée in a landslide—and had planned to campaign on the same center-leaning turf the early starting Hollande staked out first. Strauss-Kahn’s New York arrest on sexual assault charges in May atomized the scenario of the former IMF chief strolling all the way virtually unchallenged to the Elysée, with Hollande soon replacing the sidelined DSK in polls as both the favorite to win the primary, and to defeat Sarkozy next spring. On Sunday, Hollande proved the polls accurate in predicting the Socialist result.

To prove the pollsters right next spring, however, Hollande will have to overcome some legitimate criticism from the right. For example, in contrast to Sarkozy—who had deep, wide-ranging cabinet experience before assuming the presidency—Hollande has only served as a regional official and legislator (as well as PS leader). As a result, Hollande has no hands-on international work or exposure to take into his presidential campaign (another point he shares with Obama). Meanwhile, though his unaffected, affable, and accessible nature may compare well to the fractious Sarkozy style that voters have soured on, Hollande’s British-hailed profile “Monsieur Normal” may well prove a bit too undistinguished and ordinary for a presidential role the French still regard as almost monarchical. Polls indicate the French like and respect candidate Hollande, but he must still convince voters he has the unique stature of Président. And as he does that, of course, Hollande will have to find a way to defend his proposals (and his person) during six solid months of withering attacks from France’s street-fighting conservatives, whose televised offensive Tuesday was scarcely a warm-up. But simple defense won’t be enough: the relatively untested Hollande will also have to find a convincing manner of arguing he has the answers for confronting an on-going international economic and financial crisis that has French voters seriously rattled.

Does all that add up to mission impossible—especially given the tendency of people to err to caution with the devil they know in times of crisis? Could be, but it’s worth pointing out that, for now, the odds remain on Hollande’s side. He not only came out of the PS primary on top, but also enjoying the backing of all his Socialist rivals and the factions they represent. That may well help further increase his lead in polls that–even before the primary–showed him defeating Sarkozy in the general election by a relatively comfortable margin. In other words, things look rather positive Hollande at this point, even if the hardest part of his battle still lies ahead. For that reason, he’d probably be well advised to continue brushing off foreign-origin contributions to his cause like “Monsieur Normal”, and instead find some inspiring and mobilizing French version the American import, “Yes We Can”. For better and worse, it’s a better fit.