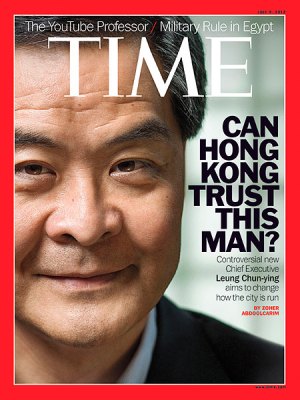

Hong Kong Chief Executive elect Leung Chun-ying leaves the government headquarter's after a meeting with Chief Executive Donald Tsang in Hong Kong on March 26, 2012

Leung Chun-ying, often referred to as C.Y. Leung, is Hong Kong’s incoming Chief Executive. It’s a pressure cooker of a role that puts him at the helm of the freest and most international city of the world’s most populous nation, during times of economic uncertainty to boot. The 57-year-old former surveyor faces a daunting task. Immense income inequality, ruinously high property prices, an entrenched business oligarchy and a sophisticated population that aspires to greater political participation than the present system allows for: these are just some of the issues and stumbling blocks that could thwart his stated aim of bringing greater prosperity, equality and social cohesion to a feisty, semiautonomous region of 7 million. And he must do it under the scrutiny of both Beijing’s unblinking gaze and Hong Kong’s notoriously cutthroat press.

Leung’s humble beginnings — he is a police constable’s son — have endeared him to large sections of the Hong Kong community, but there are many who resent his close ties to Beijing and he has even been accused of being a crypto-communist. He is also embroiled in a scandal over unauthorized alterations to his luxury home on Victoria Peak, reports of which first surfaced in local press on June 19. Residential refurbishments may not sound like the stuff of political controversy, but when Leung’s poll rival Henry Tang confessed, at the height of his campaign, to illegal modifications to his home, it cost him the trust of a public that demands its leaders abide by the same onerous red tape as everyone else. Although Leung’s renovations were not as substantial as Tang’s, their existence is seen as a baffling lapse of judgment on Leung’s part, and critics are already calling for his resignation.

In an exclusive interview with TIME’s Zoher Abdoolcarim, Liam Fitzpatrick, Joe Jackson and Vanessa Ko, which took place on June 5, this often divisive figure reveals his plans for greater harmony.

(Cover Story: Can Hong Kong Trust This Man?)

What are the three things Hong Kong needs most?

Community building, a broader outlook on the future and a slightly more proactive role of government in economic development. I want to build the community across the various social strata, and also across the various ethnic groups. That would be the first thing. Secondly, we must put short-termism behind us. We have never looked long term — never in the history of Hong Kong. We must ask ourselves [for future generations], What should the coastline and topography of Hong Kong look like? Reclamation, opening up the countryside, infrastructural projects, community facilities, so on. We should start doing that kind of planning. Thirdly, my government will adopt a progrowth policy, to the extent of investing in enterprises. We should use a small part of our fiscal reserves to kick-start certain industries. We also need to make social investments. We need to plan for Hong Kong as an aging society in 10 or 20 years time. Another form of social investment would be cleaning up the environment.

You talk about building a community, but surely Hong Kong already has a sense of community?

Unlike other British colonies — ex-colonies — we did not become a new nation. And therefore there wasn’t a new national identity. There wasn’t a new citizenship. But I think Hong Kong needs to pull everyone together so that we do have this community spirit and that we share in a common fate, a common destiny.

Big business is concerned about interventionist government. What would you say to them to reassure them?

My policies are aimed at facilitating growth of Hong Kong’s overall economy for the benefit of both big and small to medium-size enterprises. I’m not trying to tip the playing field in favor of any group.

Does more affordable housing play a role in your vision of a more equitable society?

More affordable and more comfortable. The average unit size is too small to match Hong Kong’s state of economic development, and people are crying out for more elbow room. It applies not just to our housing stock. It applies to our workplaces. It applies to our hospitals, schools and so on. We have a very low standard of space per capita. Everywhere you look, people are crying out for more space.

(SPECIAL: Hong Kong 1997-2007)

There is a sense among some sectors of society that under you freedoms are going to be curbed in Hong Kong — that you are a stalking horse for China. Tell us what your response is.

I’d like to prove people who are apprehensive about me and my government wrong again, much in the same way as they have been proved wrong in the last 15 years. Before 1997, some people were publicly claiming that they would be put behind bars [after the resumption of Chinese sovereignty], or not be allowed to return if they left. Some people even feared that certain books or magazines would not be read in Hong Kong and that the Chinese government would somehow monitor the Internet. They’ve been proved wrong, and I can prove them wrong again.

Under Article 23 of the Basic Law, Hong Kong is required to enact antisubversion legislation, which critics say will curb freedoms. Do you intend to see this legislation through?

We need general acceptance in Hong Kong before any law enacted in accordance with Article 23 has any meaning. It’s not on my agenda.

How do you make the bridge between Hong Kong and China stronger?

I coined a phrase some 16 or 17 years ago, nei jiao. It means internal diplomacy. If we were a country, which we are not, China would be the single most important element in our foreign policy architecture. It would be even more important than Malaysia is to Singapore. But we are not an independent country, and therefore this is not foreign relations; it is internal diplomacy. In our interface with the mainland, many things are conducted like they are conducted in foreign relations. The relationship must be a managed relationship. [At present] we are not doing this internal diplomacy properly. We need to start with the [mainland Chinese] people to explain Hong Kong’s case to them, and Hong Kong’s role in the country.

What is Hong Kong’s role within China?

We are still a model in ways economic and noneconomic. When I say things noneconomic, I would include governance — and rule of law is a key element. Many, I sincerely believe they tell the truth, say that they still look to Hong Kong for inspiration.

Why is it that there’s a certain section of society that, no matter what you do or say, does not trust you and even fears you? How are you going to win them over?

I shall do more reaching out, do more open communication. It is important. I can’t shake the hands of everyone in Hong Kong and I can’t speak face to face, eye to eye with everyone, but I shall try to do my very best. Why? Two things. Hong Kong people have always had, and for good historical reasons, a healthy dose of skepticism when it comes to their political leaders. Secondly, perhaps people see me as not a typical Hong Kong person. In my early days, as a young graduate, I spent most of my spare time running up and down the country giving lectures for free, paying for my own train fares, airfares to share what I had learned. [I’m] not a member of the Communist Party, but I’ve spoken at Communist Party cadre schools, talking to mayors and ministers about land and housing matters and how free-market forces allocate the use of land and housing. I’m also not typical in the way that I don’t have a foreign passport and never have. I never left Hong Kong — never emigrated, never looked to emigrate — and all my three children were born in Hong Kong. All these are not typical for someone of my background.

(MORE: Hong Kong’s Non-Election: A ‘Rotten’ System on Show)

Low-income people tend to like you or at least want to give you a chance. Members of the elite seem to be more distrustful. Is it because you are the son of a policeman?

I hope not. Many people in the elite group still don’t believe in statistics. They don’t believe that we have abject poverty in Hong Kong. They don’t believe that half of the workforce in Hong Kong earns no more than 11,000 Hong Kong dollars a month [$1,400]. When I was supporting legislating for a minimum wage using facts and figures, many people in the elite said, “C.Y., the figures must be wrong because I don’t know anyone who earns less than $10,000.” The so-called elite in Hong Kong has what we call “Central District values,” and I think Hong Kong would do a lot better if everyone could just travel out a bit and see how, not just the other half, but probably the other 75%, lives.

If you had to name one single thing in your background that drives you, could you?

We were living in policemen’s married quarters in 1966. My father was turning 65, and a few years before that we came to realize that as soon as he retired, we would have to move out of the quarters. And public-housing policy at that time was such that retired officers were not allowed to apply for public housing. So there were two options. One was to hang on for as long as we could and protest against the eviction, which most of my neighbors did. And the other option was to fend for ourselves. My mother mobilized the entire family, and we worked around the clock at home piecing together plastic flowers and toys. I was 10 or 11 in those days, and I carried packs of materials back home from the factory — a 20- or 25-minute walk as a young boy. Nowadays it’s called child labor. But the family made as much as my father’s salary, which was 300 Hong Kong dollars a month [nearly $40 in today’s exchange rate]. So by the time my father retired, we had enough money to pay for a small 450-sq.-ft. unit in [the once largely working-class district of] Kennedy Town. My father’s colleagues marched up to Government House to petition for their housing needs. We didn’t do that. [We were] self-reliant.

What would you be doing if you weren’t Chief Executive?

I’d probably be somewhere in England now, where my children are — we have three children, all at university, the eldest doing Ph.D. research in stem cells, two others doing their first degree. My wife’s in England, she goes there a lot because home is where the children are. She’s a lawyer by training. But two years ago, a junction suddenly appeared on the road. I was working at this professional consultancy looking after the Asia-Pacific region. And they said, “C.Y., we’d like you to take over and be the next chairman of the board of a global company.” Tempting. I would probably have a bachelor flat somewhere in London and I would buy a small working farm somewhere in the West Country, and I’d work Monday to Friday in London and spend time on the farm with the family on weekends. Heaven on earth. But if I turned into that junction, it would be — as far as my public service in Hong Kong is concerned — the point of no return. So I made the decision [to run for office]. It was the call of duty.

What is the most challenging issue facing the Hong Kong government?

Disengagement with the people. People are disenfranchised because they don’t vote, they are disengaged because we don’t talk to them, and we don’t listen, not directly. There is a sense of being disowned, and therefore, there’s a deep sense of distrust between the people and the government, or by the people of government. I want to bridge that gap and I want to re-engage with the people.

Isn’t it ironic that a sometimes divisive figure has been tasked with healing a divided city?

It’s a fair point. It’s a very good way of putting it. But we have to start somewhere.