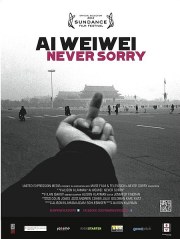

Chinese artist and dissident Ai Weiwei walks out of his studio in Beijing on Nov. 15, 2011

Expressions United Media

Last week, Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, a documentary about China’s leading dissident artist, debuted in U.S. cinemas. Its young director, Alison Klayman, an American living in Beijing, followed Ai for the better part of three years. She sees him both receiving accolades for his art in Europe as well as the blows of police truncheons for his efforts in Sichuan province, where he and others sought to document the death toll of a devastating earthquake whose full extent authorities were alleged to have obscured. Klayman’s widely acclaimed portrait of Ai is both that of an artist of international repute and a man who lives a curtailed life at home, surrounded by secret police, surveillance cameras and a vast pack of stray cats. Klayman spoke with TIME about her experience getting to grips with one of the world’s most unique — and important — public figures.

TIME: Ai Weiwei apparently screened the film at home in Beijing. Are you relieved, after all these years, that he seems to like it?

Alison Klayman: He saw it before Sundance [in January], and he didn’t ask to change a single thing, which was a good sign. And he seemed impressed by the editing and how it was all put together and how dense it was and how much we fit in of his life. But what I think has really excited him, now that we’re more than half a year later, is how well the film is doing around the world and how he gets to see people reacting to it every day. I don’t have to send him a digest of where the film is playing this week or what the reaction has been, because he’s on Twitter, he sees all of it. And I see him, for example, retweeting some woman’s blog post who just saw it in San Francisco. He gets to see all these things in real time, and I think that excites him, well beyond just what he thinks of the movie itself.

(PHOTOS: Ai Weiwei’s Photographs)

What was it like encountering a figure of his celebrity and reputation for the first time and then setting about documenting him for three years?

Literally, the first day I met him was the first day that I started filming; I came along with a team from a local gallery in Beijing, and they asked me to make a video to accompany a show. So from Day One, I never had to do any convincing, which I imagine would be very hard to do, actually. He’s someone who, even from the very first meeting, you can tell has this very commanding presence, and he can be very intimidating. I had heard he can make an interviewer cry if he doesn’t feel obliging. But on the other hand, being around him, you also felt he really wants to have a good time — he really does want to put people at ease. And I think you see that in the film a lot.

A recurring theme in the film is how media savvy he is, how comfortable he is before the camera and as a public figure. Do you think you got to see beyond that?

I think it meant that from the very beginning I had to approach the project with a lot of skepticism. There were times when you have to be questioning of him, because it’s so clear that he’s so media savvy and you just have to wonder. His art deals with the fake and the real — his company is called Fake Design. But I think I get these quiet moments with him or moments when he’s with his mother or eventually with his son, and that was imperative for this project because he is already covered in so many ways.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=0MYFOzP6Xns]

What are some of the common threads linking his art and his politics?

There are a couple words that come to mind: one is communication and the other is the individual or individuality. In China, the official line is, “Look, you know, how far China has come and all the ways that China has improved, and this is a gradual march of progress for society getting better as a whole.” And I think Ai Weiwei’s argument is that he doesn’t want to talk about a society that’s getting better as a whole if it doesn’t care about the individual, about the dignity of one person’s life and individual rights and individual expression.

And so much of what his art and activism is about is communicating what he thinks, but also engaging other people to jump into the dialogue, to use their voice and to value their individual ability to express themselves. I never once saw him do an interview with CNN or al-Jazeera or BBC where he didn’t first and foremost identify himself as an artist. I never heard him say, you know, “Let me take off my artist hat for a second and tell you what I do think about the government.” It was all part of the same thing.

Is that, in part, how he gets away with it?

Well, it’s funny because that’s a question I asked a lot, and I would always get rebuked by him if I ever phrased it as “getting away with it.” He did have his blog shut down and get beaten up by the police. He was detained for weeks. But I wondered from the very first week I met him: How does he accomplish what he accomplishes? And a lot of his peers, their answer to me was, “Because he’s an artist.” For the authorities, their primary concern with Ai Weiwei is his impact on a domestic audience. His being on Twitter or his talking [provocatively] to the foreign press is one thing. The people who really get into trouble [like jailed Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo] are those who are very specifically writing down and articulating in Chinese what their criticisms are, they’re organizing people, they’re talking about alternative political structures and the very specific layout of how reforms would go and how democracy would look in China. Ai Weiwei has always spoken very directly and does organize people, but he’s not a political-reform leader. He’s not going to lead the opposition party, and he wouldn’t, because he’s an artist.

(MORE: Chinese Activist Ai Weiwei Loses Appeal on Tax Charge)

What I think has gotten him into trouble is when he has started to organize people online and really put into words certain things that he’s upset about, as opposed to letting a visual-art piece speak for a much more complex message. When he’s actually organizing people to go out to Sichuan and is putting online the documents that he’s been sending to the government and posting their responses and making these films — that’s the more dangerous territory.

He does seem to have mastered walking that line between art and politics. He documented, artfully, his own farcical quest to seek justice through official channels in Sichuan. Can you talk a bit about what he’s doing here?

There’s this quote he unfortunately never said to my camera about [surrealist artist Marcel] Duchamp, who is one of his heroes and main influences. He said, “In my case, China is my Readymade” [referring to a series of Duchamp’s subversive early 20th century works]. And I always that thought that was exactly on point. What he does is set the conditions and sees what happens. You just take what exists, and if you’re putting it in the right context and you’re setting up the conditions — putting the urinal in the museum or putting the bicycle on the stool or whatever — then everyone talks about it and thinks about it. It’s the same for [Ai]: he’s filing a complaint and going through the mundane, absurd processes of the system and documenting it to see how it plays out. It’s artistic, it’s his Readymade, because of the way he’s playing with the situation, toying with levels of truth and reality.

But then there’s also the side of him I observed where I do think he is a genuine political organizer and activist. People go to him, other activists and lawyers all come to him for advice. It’s crazy, you wouldn’t have imagined this. You meet the curators of the Haus der Kunst and the Tate Modern but you’re also meeting all of China’s top rights lawyers and these petitioners and hearing about all the stories of these other types of political dissenters. [Ai] is saying, Look, China has a problem with rule of law and a problem with transparency and a problem with being willing to acknowledge the truth and being willing to seek it out through the system.

(MORE: Tax Trouble: China Orders Artist Ai Weiwei to Pay $2.4 Million)

Given what he’s up against — firewalls, surveillance, detention — is it inspiring following him around and watching him work?

For the activists, volunteers and others working with him, it always seems to be an emboldening experience to be around Ai Weiwei. It was for me as well. They were seizing on the very tools that I’m interested in: documentation and the whole aspect of transparency in social media. He rarely complained about me being in the way, he rarely said, you know, “Alison, you’re always in my face, you’ve got to get away.” Instead, he made fun of me a few times when I asked, “Well, is it O.K. if I come? Do you think it’s O.K.?” He’d be like, “God, you ask permission so much.”

There’s a story that Weiwei told me that I think of before all his other amazing quotes that are in the film and the cool artwork that he’s done and all the ways that he can be inspiring: there’s this one story that I think will always stay with me. It’s what he said to one of his cameramen the night when the police [in Sichuan province, in a scene documented in the film] raided everybody’s rooms on their floor in the hotel, and afterward [Ai] said to his cameraman, “Did you get any footage of it? Did you record any of it?” Weiwei recorded it with an audio recorder because that was the only piece of equipment he had in his room, and that’s why there’s just an audio recording of it. And the camera guy said, “Well, I was nervous that they were going to take the camera, so I didn’t take it out.” Weiwei said, “Well, in that case, it’s like they already took it to begin with.” He was much more concerned about getting the story, getting the image, getting the truth. It’s hard not to feel emboldened by that.

MORE: To Help Dissident Artist Ai Weiwei Pay Tax Bill, His Supporters Try Microlending