Indian troops training for the border war with China.

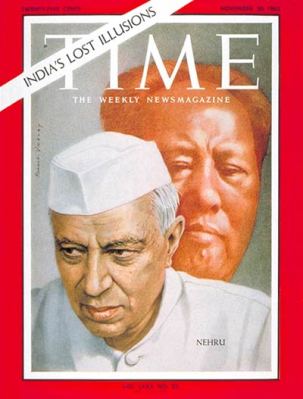

The only major war in modern history fought between India and China ended almost as abruptly as it began. On Oct. 20, 1962, a multi-pronged Chinese offensive burst the glacial stillness of the Himalayas and overwhelmed India’s unprepared and ill-equipped defenses, scattering its soldiers. Within days, the Chinese had wrested control of Kashmir’s Aksai Chin plateau in the west and, in the east, neared India’s vital tea-growing heartlands in Assam. Then, on Nov. 21, Beijing called a unilateral ceasefire and withdrew from India’s northeast, while keeping hold of barren Aksai Chin. TIME’s Nov. 30, 1962 cover story started off with a Pax Americana smirk: “Red China behaved in so inscrutably Oriental a manner last week that even Asians were baffled.”

(PHOTOS: China and India’s Clash on the Roof of the World)

Fifty years later, there are other reasons to be baffled: namely why a territorial spat that ought be consigned to dusty 19th century archives still rankles relations between the 21st century’s two rising Asian powers. Economic ties between India and China are booming: they share over $70 billion in annual bilateral trade, a figure that’s projected to reach as much as $100 billion in the next three years. But, despite rounds of talks, the two countries have yet to resolve their decades-old dispute over the 2,100-mile-long border. It remains one of the most militarized stretches of territory in the world, a remote, mountainous fault-line that still triggers tensions between New Delhi and Beijing.

TIME

At the core of the disagreement is the McMahon Line, an imprecise, meandering boundary drawn in 1914 by British colonial officials and representatives of the then independent Tibetan state. China, of course, refuses to recognize that line, and still refers much of its territorial claims to the maps and atlases of the long-vanished Qing dynasty, whose ethnic Manchu emperors maintained loose suzerainty over the Tibetan plateau. In 1962, flimsy history, confusion over the border’s very location and the imperatives of two relatively young states—Mao’s People’s Republic and newly independent India led by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru—led to China humiliating India in a crushing defeat where, by some accounts, both sides lost upwards of 2,000 soldiers. In 1962, TIME described the Chinese offensive as a “human-sea assault,” like a “swarm of red ants” toting burp-guns. Beijing seized and has never relinquished Aksai Chin—”the desert of white stone”—a strategic corridor that links Tibet to the western Chinese region of Xinjiang. “The India-China war took place through a complex series of actions misunderstandings,” says Kishan S. Rana, a former Indian diplomat and honorary fellow at the Institute of Chinese Studies in New Delhi. “Bilateral relations are, however, moving forward. The border, despite unresolved issues, today is a quiet border.”

(MORE: India’s troubled Northeast—a future global flashpoint?)

Yet, just as China’s economic liberalization hasn’t led to an opening up of its political system, the strength of India and China’s trade ties have yet to unwind the border impasse. The border may be “quiet,” but tensions have spiked in recent years, with China reiterating its claim to almost the entirety of Arunachal Pradesh, a northeastern Indian state that the Chinese overran in 1962 and consider to be “Southern Tibet,” while India has steadily beefed up its military deployments in the long-neglected Northeast. The issue of Tibet casts a long shadow—in 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to India, an accommodation that Beijing still resents. When he went recently to speak at a historic monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, the Chinese government lodged a formal complaint. “The territorial dispute between India and China is intertwined with the Tibet issue and national dignity, making the whole situation more complicated,” says Zhang Hua, a Sino-Indian relations expert at Peking University. “When the two countries look at each other, they cannot see the counterparty in an objective and rational view.”

(MORE: Tibetans, the orphans of the Sino-Indian war.)

That nationalist ill-will is not just confined to those in the corridors of power. In a survey published last week, the Pew Global Attitudes Project found that 62% of Chinese hold an “unfavorable” view of India—compared to 48% feeling the same way of the U.S. Brahma Chellaney, a professor of strategic studies at the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi, fears such sentiment driving the political calculus in Beijing. In a more heated climate, the Chinese leadership may not be immune to the calls of its more hardline nationalists to strike out at India, writes Chellaney:

For India, the haunting lesson of 1962 is that to secure peace, it must be ever ready to defend peace. China’s recidivist policies are at the root of the current bilateral tensions and carry the risk that Beijing may be tempted to teach India “a second lesson”, especially because the political gains of the first lesson have been frittered away. Chinese strategic doctrine attaches great value to the elements of surprise and good timing in order to wage “battles with swift outcomes.” If China were to unleash another surprise war, victory or defeat will be determined by one key factor: India’s ability to withstand the initial shock and awe and fight back determinedly.

China’s decision to withdraw from much of the territory it seized in 1962 was spurred by the arrival of significant amounts of aid and weaponry in India from the U.K. and the U.S.—Washington, at the time, was locked in the Cuban Missile Crisis, an imbroglio some historians suggest China exploited to its advantage in launching its assault. TIME’s 1962 cover story on the Sino-Indian war breathes fire on the 73-year-old Nehru—”his hair is snow-white and thinning, his skin greyish and his gaze abstracted”—and his “morally arrogant pose” of “endlessly [lecturing] the West on the need for peaceful coexistence with Communism.”

(MORE: Is war between India and China inevitable?)

An inveterate Cold Warrior, Henry Luce’s TIME reckoned the chief lesson of the war ought to be the demise of Nehru’s policy of Nonalignment, his principled Socialist stand with a number of other recently independent states to chart a third path on the world stage, away from the influence of both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. (I’ve written about nonalignment at length here, here and here.) “Nehru has never been able to rid himself of that disastrous cliche that holds Communism to be somehow progressive and less of a threat to emergent nations than ‘imperialism,'” TIME declared. His dreamy belief in Asian solidarity and unwillingness to see who really were “India’s friends”—namely, the U.S.—led to India’s humiliation. Tellingly, the TIME 1962 story hopes for the Indian army to “emerge as something of a political force” in its own right: for many Americans during the Cold War, the grand struggle against Communism outranked any concern for the future of fledgling democracies.

The shock of the war with China is believed to have worsened Nehru’s health; he died less than two years later. But his gift to India—its democracy—has endured and its military—unlike that of neighboring Pakistan, which would be drawn much more firmly into the American camp—has avoided meddling in its politics.

(MORE: India, China and the new world order.)

The war’s real legacy lies less in the folly of Nehru’s ideals and more in the frozen landscape where the battles were fought: India and China’s restive borderlands remain the victim of the two countries’ longstanding dispute, locked down by vast military presences. In Tibet and Xinjiang, any trace of dissent or separatist ethnic nationalism is ruthlessly suppressed. In Indian Kashmir and in its northeastern states, emergency laws are still in effect—that small bonus of being able to vote somewhat dampened by decades of army occupation, woeful governance and inadequate investment in basic things like infrastructure. TIME, in 1962, described the journey down a “Jeep path” in Assam where it took 18 hours to cover 70 miles. Fifty years on, the conditions haven’t improved much in many parts of the Indian northeast; New Delhi’s belated efforts to transform the region into an economic hub with Southeast Asia have yet to take hold.

Long gone are the days when caravans would regularly depart from Ladakh, in what’s now Indian Kashmir, and wind their way around the mountains toward the Silk Road cities of Yarkhand and Khotan, now in Xinjiang. Tibetan monks in Lhasa can’t visit some of the most sacred sites of their faith that lie in the Indian northeast. The myriad connections that bound the communities living along the Indian-Chinese border, the veritable “roof of the world,” have been lost amid New Delhi and Beijing’s icy standoff. As one Member of Parliament from Arunachal Pradesh told me earlier this year, “There’s a lot we shared in common, but that’s now all a thing of the past.”

—with reporting by Nilanjana Bhowmick/New Delhi and Gu Yongqiang/Beijing