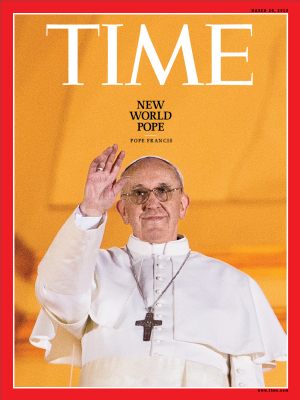

Newly elected Pope Francis I on the central balcony of St Peter's Basilica on March 13, 2013 in Vatican City, Vatican.

Jorge Mario Bergoglio almost made history eight years ago. According to several accounts, he had been the only real contender against Joseph Ratzinger in the first round of balloting that led to the election of the German as Pope Benedict XVI in April 2005. That itself was history: Ratzinger became the second consecutive non-Italian as head of the Roman Catholic Church. Now Bergoglio has now made history twice over with his own election as Pope Francis. The Argentine is the first man from the Western Hemisphere to become Pontiff. And, as the son of Italian immigrants, he has won the Papacy back in the land of his ancestry. In his first address, the traditional Urbi et Orbi—to the city and the world—he chided his brother Cardinals for going “to the end of the earth” to find the new Bishop of Rome. But there was a kind of subtle, rounded—perhaps divine—justice to it all.

Bergoglio was a surprise. Every 21st century technology seemed to have been focused on the chimney above the Sistine Chapel—a system put in place in 1939 that spouted smoke signals to communicate its message. And new and old media was bandying about other: the Cardinal of Milan who had seemed to have been promoted quickly through important offices by the retired Benedict XVI; and the Cardinal of Sao Paulo in Brazil, a favorite among the bureaucrats of the curia. Even another Argentine Cardinal was more favored than Bergoglio. But as the old saying goes, he who enters the conclave a Pope, leaves it a Cardinal. Everyone had overlooked Bergoglio, 76, believing he was too far along in years and that his moment had passed. It has only just begun.

(WATCH: TIME Video: How Pope Francis Was Elected )

The accession of a new Pope is always cause for wonderment—if only because the papacy of the Roman Catholic Church has managed to survive more vicissitudes than almost any other kingdom in history. No other institution can claim to have withstood Attila the Hun, the ambitions of the Habsburgs, the Ottoman Turks, Napoleon Bonaparte, Adolf Hitler in addition to Stalin and his successors. Every new pope pushes that longevity forward, through fresh crisis and challenge. And in the 21st century, he does so at the head of a spiritual empire that touches more than 1 billion souls and whose influence crosses borders and contends with other principalities and powers

The weight of history—while majestic—makes the Papacy less than nimble in a world literally rushing forward with the speed of pixelated light. Pope Francis must deal with headlines reminding him of the church’s severe shortcomings in dealing with the scandal of priestly sexual abuse even as he has to try to reform the Vatican’s finances by way of a bureaucracy that originated in medieval times and is burdened by aristocratic privilege and the Machiavellian instincts of feudal Italy. He must respond to the opposing demands of a divided flock—with many Catholics in North America and Europe asking for more liberal interpretations of doctrine even as many Catholics in the burgeoning mission fields of Africa and Asia warm to the conservative comforts of the faith. Unlike the cataclysmic challenges in the church’s past, these problems are internal but, as such, much more difficult to resolve. And then there is the unprecedented figure of his old Conclave rival, the Pope emeritus—distinguished and professing to be silently retired, yet still an embodiment of a conservative legacy that will be difficult to touch while he remains alive. With all this to handle, countering Napoleon and the Turks might well have been easier.

(PHOTOS: Pope Benedict’s Final General Audience)

Is Francis up for the task? The fact that he held his own in balloting back in 2005 against the formidable Ratzinger shows that he has always had the respect of the Cardinals—and indeed he has enough years of work with the secretive and sclerotic Roman Curia, the Vatican’s bureaucracy, to be able to work with it.

He will also bring much needed oxygen to parts of the Catholic empire. Just before the Conclave that elected him convened, he celebrated his 55th year of joining the Society of Jesus—whose members are popularly called Jesuits. That itself is a matter of rejoicing for the order—even though Bergoglio is on the conservative end of the often liberal Jesuit scale. The order has seen its once formidable influence wane as the star of Opus Dei rose during the reign of John Paul II. Bergoglio’s choice of regnal name too is telling. Many people immediately saw the reference to the great saint of the church, Francis of Assisi. But anyone raised by the Jesuits would have heard the resonance of another great saint and member of the Society of Jesus: the great evangelist to Asia, Francis Xavier.

(PHOTOS: The Catholic Church in the Modern World)

More importantly, the great burst of energy that Bergoglio brings will sweep into his home continent of South America, where Roman Catholicism is losing ground to the combined forces of secularism and Pentecostal Protestantism. From Tierra del Fuego to the U.S. border with Mexico, the Catholic Church has been hemorrhaging worshipers to evangelical congregations. According to Latinobarometro, in 1996, Latin American countries were 80% Catholic and only 4% evangelical. By 2010, Catholics had dropped to 69% and evangelicals had risen to 13%. Brazil, the country with the most Catholics in the world, could once boast of 99% adherence to Rome. Today, Catholics number 63% to a Pentecostal surge of 22%. Latin American prelates have always looked slightly askance at the charismatic fervor of the Pentecostals and have been reluctant to compete in kind. Bergoglio may be able to use some of the popular enthusiasm from his historic election to rekindle the faith in Latin America.

The question of fealty, however, remains key to the Church. As enormous as it is, it must deal with the fractious faithful—many of whom find Rome and the Holy See more and more distant from their everyday lives. The entrenched priestly sex abuse scandal and the unplumbed depths of the Vatican’s finances only seem to turn off more Catholics by the day. Perhaps Francis can return to the Gospel reading for the Sunday Mass before the conclave, a selection read in Catholic churches around the world. It was the parable of the prodigal son. Many Cardinals use it to talk about bringing back Catholics who had left the church. The church itself may have to discover that it has been prodigal and find a way to return to its people.