Updated August 4, 04:40 a.m. EST: In response to these threats, Twitter has amended its policies and the company says it will put extra staff in place to handle reports of abuse, which from next month may be logged across all platforms via an “in-tweet” report button, enabling Twitter users to report abusive behavior directly from a Tweet.

I have been told to expect a call today. The Major Crime Unit handling my case is handing it over to the Anti-Terror Branch of London’s Metropolitan Police Service, and the new team will brief me. A helpful cop based at the police station nearest my London apartment called twice yesterday afternoon with updates on the investigation. He told me a police squad car would drive by my apartment block for a second night, to make sure everything looked calm. The problem with a bomb threat, even one lacking in credibility, is that the authorities must take it seriously. Incredible threats occasionally prove true, and just making such a threat already constitutes a breach of more than one British law.

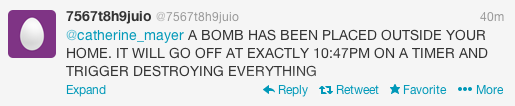

Dick Dastardly might have scripted the threat I received via Twitter on Wednesday evening:

(Another Twitter user riposted, “oh s**t not everything, that’s really bad.”) It was a cartoonish warning and in notifying the police, I set the weighty analogue wheels of justice in motion in pursuit of a puny digital miscreant. Welcome to the real-life Wacky Races.

So should I have reported the threat at all? My first instinct was to do exactly as Emma Barnett, Women’s Editor of the Daily Telegraph, recipient of an identically-worded tweet: she shut her computer and went to the pub. I reluctantly rang the police after Twitter users alerted me to tweets from two other female journalists, the Guardian‘s Hadley Freeman and the Independent‘s Grace Dent. Both had been threatened too and Freeman had already notified Scotland Yard. She tweeted me: “They said we should all make reports and it’s an arrestable offense.”

The officer who took my original call, the kindly pair of female cops who came to take my statement, and the police liaison at my local station all vigorously reinforced that message. The bomb threats – sent from different Twitter accounts to at least eight women, including me – followed rape threats levelled at campaigner Caroline Criado-Perez and Labour MP Stella Creasy after they joined forces in a successful push to keep a female figure, apart from the Queen, on British banknotes. Criado-Perez received a bomb threat too, although the imaginary device outside her home was described as a car bomb due to explode 17 minutes after the fictitious timer-and-trigger devices described in most of the warnings. To ignore such harassment, said my friendly local policeman, would “send out the wrong message.” He was the first to voice an assumption shared by victims and police, that the person who posted the threats is male. “There are men who sit in dark rooms doing these things,” he said.

A new frontline in the gender war has opened, and it is located in the strange landscapes of Twitter. The police find themselves conscripted into the battle, but most forces lack the knowledge and equipment to fight effectively. Although the Met has its own Twitter feeds—the main one is @metpoliceuk—not one of the officers I’ve encountered uses Twitter or understands why anyone would wish to do so. The first officer mistook the miscreant’s Twitter handle for a code; the more technologically savvy of the two female cops referred several times to his “IIP address.” (The hoaxer’s IP address, the unique number assigned to his computer or smart phone, will be known to Twitter unless he took the precaution of concealing it.) The officers were unanimous in advising me to take a break from Twitter, assuming, as many people do, that Twitter is at best a time-wasting narcotic, whose addled users tweet photographs of churches that resemble surprised chickens or post photographs of their breakfast.

Twitter is, of course, exactly that, but it is also an interactive communication medium that, for journalists, ranks with the telephone and email as an essential tool of the trade. Deployed cleverly, it is also an effective rallying mechanism, as Criado-Perez and Creasy demonstrated. Across the world, growing numbers of women turn to Twitter to connect with each other, compare experiences and sometimes to combine forces to try to bring about change. One of my favorite feeds is @EverydaySexism, which documents the incidences of harrassment, disparagement and patronising behavior that women encounter on a daily basis. Feminism and Twitter are natural partners.

But trolls are equally at home on Twitter. A medium that restricts arguments to bursts of 140 characters and promotes hashtaggable sentiments was always going to encourage virtual shouting matches. The apparent anonymity of Twitter tempts the angry and bored into thinking they can vent with impunity. Virtual sticks and stones can hurt, by intimidating or defaming their targets or inciting others to real violence, and sometimes the only recourse is to the law. For Criado-Perez and Creasy, targeted with an exceptional volume of exceptionally nasty tweets, the Twitter self-defense option of retweeting and shaming abusers under the hashtag #ShoutingBack simply wasn’t enough.

Yet inevitably the debate engendered by their experience and further fueled by the bomb threats has swung into dangerous territory. Twitter is rolling out a “report abuse” button, a good idea if it makes the company more responsive to genuine complaints (at time of writing, on Friday morning, Twitter has not replied to my report Wednesday evening of the bomb threat). However, Twitter has many times over proven itself as a vital vehicle for free speech in situations where free speech is under threat—Iranian protestors provided the template in 2009. Any apparatus geared to quashing abuse risks censoring flows of information.

And there’s the question of best use of police resources. They certainly weren’t well deployed pursuing Briton Paul Chambers, who in 2010 made an unfunny but obvious joke about blowing up Robin Hood airport in northern England after flights were canceled. Only after two years and three appeals—and a Twitter-based campaign, #TwitterJokeTrial—was his conviction quashed.

Chambers did not intend to frighten anyone. The motives of the person who tweeted me and the other women are harder to gauge, but presumably he wanted a reaction and in that respect he’ll have been richly satisfied. Which is a shame. In most cases #IgnoringTheIdiots is a better strategy than #ShoutingBack.

I alerted police because I believe, as @EverydaySexism illustrates, that the accretion of small iniquities adds up to a gross injustice. Even we privileged women in countries with laws to protect us live as second-class citizens. There were other factors that also influenced my decision-making, not least the apparent eagerness of the police to take action on Twitter abuse. I’ve also seen what can happen if you don’t report aggression. As a student, I failed to tell the authorities I had fought off an attacker in the women’s toilets on campus. He later raped two women.

So when the Anti-Terror Branch contacts me today, I shall continue to give assistance to the investigation. These officers are taking over because unlike their colleagues, they are digital natives, navigating with ease through the Twitter battlefields. But I shall also make clear to them, as I have done in my previous dealings with the police, that I never took the bomb threat seriously. The problem of abuse, the deepening hostilities between men and women: these I take seriously. These are ticking bombs and we need to figure out how to defuse them.

Catherine Mayer is TIME’s Europe Editor and author of Amortality: The Pleasures and Perils of Living Agelessly.