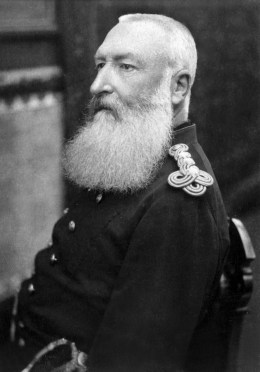

King Leopold II

It would take a determined visitor to the Royal Museum for Central Africa to locate the life-sized likeness of one of history’s most brutal colonial rulers carved from ivory. The statue of Belgium‘s King Leopold II, created at the height of his plunder in the Congo, is discreetly placed at the back of a cabinet in the dark corners of a temporary exhibition on the Congo River.

Harder to hide away are the statues built into the alcoves of the museum’s entrance hall, where the bust of the late monarch once stood. Europeans in gilded robes cradle naked African children above plaques which extol “Belgium Bringing Civilization to Congo.”

As the museum on the leafy fringes of Brussels prepares to shut down for its first major renovation since the Congo’s independence in 1960, planners are faced with the difficult task of trying to modernize an institution where reminders of the country’s violent colonial past are etched in its very walls. “On every pillar there is a double L for Leopold – you cannot just act as if we’re only dealing with contemporary Africa,” Guido Gryseels, the museum’s director, tells TIME.

Decades after their colonies gained independence, many European nations still grapple with — or attempt to obscure — their bloody imperial histories. State apologies are rare, and many institutions simply chose to ignore their connection to unsavory pasts, says J.P. Daughton, associate professor of modern European history at Stanford University. “The most striking thing about memories of colonialism in the Quai Branly in Paris and the Victoria and Albert in London – two museums that hold vast amounts of art accumulated during the Age of Empire – are the silences,” he says.

Of all Europe’s colonial histories, the slaughter in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo was unique in its aims. While the exploitation of much of Africa, Asia and Latin America happened under a flimsy guise of state-sponsored enlightenment, the Congo was Leopold’s personal property. From 1885 to 1908, he ran it as a factory staffed with disposable workers whose only purpose was to produce more ivory and rubber to fund his ever-grander palaces, statues and monuments.

When reports started emerging in the late 19th century of children’s hands being hacked off for failing to meet rubber quotas and millions of people murdered or worked to death, Leopold embarked on a zealous PR campaign. He shipped over 200 Congolese to set up “African villages” on the damp banks of Tervuren lake, and built a pavilion to promote the riches of the Congo.

The exhibition was a great success: Belgians flocked to gawk at the villages, oblivious to the fact that a few of the ‘exhibits’ were dying from the cold. The government agreed to take over administration of the Congo, which they eventually did in 1908, a year before Leopold died.

Such was the success of the 1897 exhibition that the King made it permanent, using funds from his interests in the Congo to construct the grand neoclassical building which houses the collection today. And while the museum has quietly become one of the world’s leading research centers on Central Africa, the permanent exhibition remains frozen in time. Africans are represented in stone and bronze statues as primitives and savages saved by heroic white Europeans. On one wall are the names of the hundreds of Belgians killed in the Congo. The names of the millions of Congolese victims are nowhere to be found.

Belgium’s African diaspora has been arguing for years that the racist exhibits need to be removed or better contextualized. Albert Tuzolana, a Congolese artist working with the Belgian community group Afrikaans Platform, welcomes the renovations, but hopes the changes will not be purely cosmetic. “The abuse during the colonization is the core of the problem, it needs to be repaired, we are waiting for this,” he says.

The only apology for any of Belgium’s actions in the Congo was in 2002, when the foreign minister offered “profound and sincere regrets” for the assassination in 1961 of Patrice Lumumba, the first post-independence leader, a left-wing populist, who was shot dead with the complicity of Belgian officers.

Belgium is not alone in choosing to stay silent on the worst atrocities. Sporadic apologies are usually for specific events or after court action. The Netherlands last week apologized for the execution of thousands of Indonesians by their troops in the 1940s after widows of their victims took legal action. It took a decades-long court battle before the U.K. in June apologized to Kenya’s Mau Mau for torturing them in detention camps.

Daughton says that former colonial powers are reluctant to offer blanket apologies because that could open them up to claims for financial compensation, while they also risk a backlash at home where many voters remain nostalgic for the days of empire.

That was true of Belgium until 2005, Gryseels says, when a ground-breaking exhibition at the museum directly addressing colonial abuses sparked nation-wide debate. Now he feels people are ready for change, and after government approval at the end of August, the museum will shut its doors in November for a three-year, €75 million ($100 million) makeover.

Visitors will no longer enter the museum in the rotunda where the gold statues stand. Instead, they will pass through a tunnel explaining the context of the colonial-era exhibits.

It is not just the museum’s rose-tinted vision of colonial history that is will be brought up-to-date. A third of the museum currently houses some of its vast collection of zoological specimens, many of them stuffed and roaming fantasy landscapes in 1970s dioramas. Some of these will be consigned to the store rooms, other will re-emerge along with items from the world’s largest collection of Central African ethnographic objects in zones called “Man & Society” and “Landscape and Biodiversity.”

“We will not change all of it, we’re not going to become a 3D museum, but clearly our future is working with contemporary Africa, the Africa of the future,” says Gryseels. “You don’t build a museum on nostalgia for the past.”