Former Cambodian King, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, left, and Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen wave to audience during the welcome parade to celebrate Sihanouk's return to Cambodia for the first time in 13 years in Phnom Penh , Nov. 14, 1991.

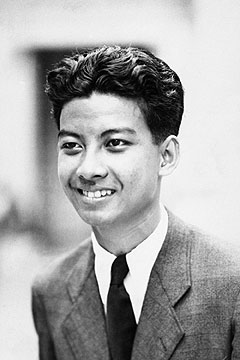

Filmmaking was a favorite hobby of Cambodia’s former King Norodom Sihanouk, and in his long, extraordinary life, he played enough roles to fill a Hollywood epic. The former monarch, who died Monday in Beijing at 89, was at various times a playboy prince, a teenage King, an independence leader, an elected Prime Minister, an exile and, later, a peace negotiator. Along the way, he found time to compose jazz tunes, throw champagne-soaked soirées and rub shoulders with the likes of Jawaharlal Nehru, Charles de Gaulle, Mao Zedong, Jacqueline Kennedy, Sukarno and Kim Il Sung. The part he loved to play most, though, was that of Samdech Euv, or Papa King, to the Cambodian people, known as the Khmer. “My people love and admire me and respect me so very much,” he once said. “They continue to believe I am a god-king.”

Though he cast himself as heroic, Sihanouk, like the country he once led and long symbolized, was most defined by tragedy. His carefully cultivated status as a benevolent and glamorous ruler was marred by his cooperation with the murderous Khmer Rouge, whose “killing fields” regime of the 1970s left 1.7 million dead. It was a decision that cost him dearly: he himself was held prisoner by the Khmer Rouge, who killed five of his 14 children. His passing is a reminder of a long-past era when Southeast Asia, not Afghanistan and Pakistan, was the focus of a protracted U.S. war. During the Vietnam War, Cambodia was carpet bombed by the Nixon Administration trying to root out “safe havens” across the border, an eerie precursor to today’s drone campaign in northwestern Pakistan.

(PHOTOS: The Rise and Fall of the Khmer Rouge)

The mercurial Sihanouk was a man of contradictions — an avowed Cambodian patriot who wrote mostly in French, a man who sought peace for his people, but whose decisions seemed to lead them, time and again, to disaster. “Sihanouk was certainly one of the most interesting leaders of the 20th century,” said Milton Osborne, author of the critical biography Sihanouk: Prince of Light, Prince of Darkness. “But I wouldn’t say he was one of the best leaders.”

Crowned King at age 18 under French rule, the young monarch surprised almost everyone by proving himself a canny political operator. He helped secure independence from a reluctant France in 1953 and then, two years later, blindsided those calling for him to give up absolute power by abdicating the throne to enter politics himself. His Sangkum Reastr Niyum party dominated the political scene for the next decade. Having secured power, Sihanouk — still in his 30s — set about becoming one of Asia’s most convivial hosts, leading Jacqueline Kennedy on a tour of the famed Angkor temples in 1967 and feting his longtime role model, Charles de Gaulle, in a 1966 state visit. He threw legendary palace parties, playing jazz saxophone along with the bands — once stopping, Osborne recalled, to announce “un petit numéro que j’ai composé moi-meme” (a little number I wrote myself).

AP

Not all was champagne and caviar, though. Sihanouk liked to refer to his country as “an oasis of peace” amid Indochina’s wars, but his authoritarian rule was riddled with corruption and decisions that sowed the seeds of Cambodia’s suffering. Across Cambodia’s eastern border, the Vietnam War was raging. Despite his declarations of neutrality, Sihanouk allowed Vietnamese communists to operate in his eastern territories, where they launched attacks into South Vietnam. The move infuriated Washington, and in 1969, Richard Nixon ordered secret carpet bombing of Cambodia. Back in Phnom Penh, Sihanouk was facing his own communist insurgency and himself derisively gave the guerrillas a name that stuck: les Khmers rouges, “the red Khmers.”

During all this turmoil, Sihanouk was increasingly distracted by his new hobby: filmmaking. In the mid- to late 1960s, he wrote, produced and directed nine films. His leading role in Cambodian politics came to an abrupt end in 1970, however, when right-wing general Lon Nol seized power while Sihanouk was abroad. Sihanouk accused the CIA of orchestrating the coup — a charge that was never proved, though Washington promptly recognized Lon Nol’s government. In exile in Beijing, Sihanouk declared support for the communist Khmer Rouge rebels he had once persecuted. The guerrillas named Sihanouk their titular head, and in 1973, Sihanouk traveled with the Khmer Rouge into rebel-held western Cambodia with his favorite wife, Monique, to pose at one of the outer Angkor temples, dressed in the rebels’ trademark black pajamas.

After the Khmer Rouge finally took Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975, Sihanouk issued a statement from Beijing lauding the victory over American imperialism. He soon returned to Phnom Penh as nominal chief of state, but he then found himself in a nightmare of unimaginable proportions. Declaring “Year Zero” in a new peasants’ paradise, the Khmer Rouge had closed the country’s borders, emptied cities and force-marched the entire populace into mass-farming collectives and executing anyone who showed signs of education. Tens of thousands were tortured to death, family life was banned and children were raised by agents of “Ankar” (the organization), led by the shadowy Pol Pot. Sihanouk and Monique, by comparison, lived well — they occasionally bought imported French food and were even allowed to keep their pet terrier — but he was effectively prisoner in his own palace. Alarmed by the carnage he saw, Sihanouk resigned his position in the Khmer Rouge government in 1976 and spent the next two and a half years in constant fear for his life.

The Khmer Rouge’s reign ended in 1979 after Vietnam, disgusted with its onetime ally, invaded Cambodia. Sihanouk was spirited out of the country and, after escaping his Khmer Rouge minders, condemned the former regime. But he also opposed the Vietnamese occupiers and founded a noncommunist liberation front that allied with the remaining Khmer Rouge armies to fight the Vietnamese. Cambodia once more descended into civil war. In exile again, Sihanouk split his time between guest palaces in Beijing and Pyongyang (North Korean dictator Kim Il Sung was a close friend), where, according to his longtime personal secretary, Chilean-born Julio A. Jeldres, he lobbied for peace as early as 1979. “He was always an advocate of talks,” Jeldres says. “But he was opposed by China, the Red Khmers and the U.S., who wanted the guerrilla warfare to continue.”

(MORE: Norodom Sihanouk: A Once and Future Prince)

By the late 1980s, with the Cold War coming to an end, all sides were finally ready to talk, and Sihanouk took on a new role as peacemaker. In 1987, he met with Cambodia’s Vietnamese-installed Prime Minister, Hun Sen, and later participated in talks that led to the 1991 peace settlement. The party Sihanouk founded, Funcinpec, won U.N.-administrated elections in 1993, but Hun Sen’s party refused to recognize the election results. Sihanouk brokered a compromise in which he would take the throne as a constitutional monarch and one of his sons, Prince Norodom Ranariddh, would share power with Hun Sen as a co-Prime Minister.

Sihanouk returned to the throne in 1993, but it soon became clear that Hun Sen had replaced him as Cambodia’s master political manipulator. Though many Cambodians respected the King as the country’s ultimate moral voice, the political factions rarely listened. Four years after the elections, Hun Sen ousted Ranariddh in a coup and has since maneuvered through several elections, some disputed, to remain in power since. The King expressed his displeasure by spending more and more time in Beijing, releasing statements that implicitly — but rarely openly — criticized the corruption and violence in Cambodia. He also repeatedly threatened to abdicate. He finally made good on the last point, stepping down from the throne for a second time in late 2004. His son King Norodom Sihamoni now reigns, but Hun Sen holds all the real power.

Toward the end of his life, Sihanouk, the monarch who once directed his country as if it were his own personal movie, was increasingly reduced to cameo appearances. History will judge how much responsibility Sihanouk bears for Cambodia’s agony or whether he, like his country, was simply a victim of history, caught between forces he could not control. “Unfortunately, I am not a god. I am a human being,” he lamented in 1997. In the end, he couldn’t script a happy ending for Cambodia.