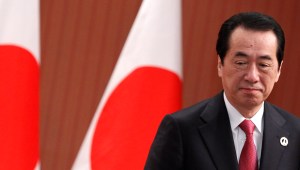

Naoto Kan, Japan’s beleaguered prime minister, has acknowledged for the first time since March 11 that he may step down — but not until he’s done doing what he needs to do.

Kan has come under increasing pressure from both inside and outside his party to give up his post after his handling of the March 11 earthquake and tsunami and continuing nuclear crisis. In a televised meeting with his party on Thursday morning, Kan said: “I’d like to pass on my responsibility to a younger generation once we reach a certain stage in tackling the disaster and I’ve fulfilled my role.” He did not indicate when that might be.

(See TIME’s full coverage of the Japan quake.)

It was an effort to save his job ahead of a no-confidence motion that took place 3PM today in the lower house of parliament. The motion, which would have required Kan to dissolve the parliament and call for new elections or resign with his Cabinet in 10 days, was voted down 293 to 152. Still, its submission by the main opposition Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and two smaller opposition groups underscores the fact that Japan’s political landscape is nearly as volatile as its geology.

In the months since March 11, Kan has come under fire for his government’s response to the crisis, from the length of time that it has taken to build temporary housing for the thousands left homeless after the tsunami to the lack of clear communication about the severity and scope of the nuclear crisis that has followed. Indeed, Kan was peculiarly absent from the public sphere during the first month of the crisis — he did not set foot in the disaster zone for weeks after the tsunami — with chief cabinet secretary Yukio Edano tirelessly facing world’s cameras. More recently, detailed reports have emerged that Kan was deeply involved in trying to prevent a full-blown nuclear fallout at Fukushima during those early days, which may account for — if not excuse — his absence.

But Kan’s political problems did not begin on March 11. When he took over as PM after Yukio Hatoyama stepped down last year, Kan entered into the nation’s “revolving door” system and became Japan’s fifth leader in four years. He inherited a divided party, challenged almost immediately from behind the scenes by long-time DPJ kingmaker Ichiro Ozawa, and he and his Cabinet faced allegations of taking improper campaign donations.

But he also inherited — and is very much a part of — a political culture that has not produced a strong leader since Junichiro Koizumi stepped down in 2006 after five years in office. The LDP governed Japan almost without interruption since the end of World War 2, until Kan’s Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) took power as part of a new ruling coalition in 2009. Hatoyama, the first DPJ PM in years, bowed out in less than a year after waffling on campaign promises to stand up to the U.S. over the relocation of one of their air bases in Okinawa. (See pictures of the political life of Hatoyama.)

That simmering problem and many others — like Japan’s weakening geopolitical role, its economy, now in recession, too-cozy ties between industry and government, and lack of opportunity for young professionals and women — have been eclipsed in the last several weeks by the magnitude of the disaster that the nation has faced. But as some normalcy returns, they are resurfacing: just yesterday, the IAEA released a preliminary report that found that the overlap between the regulation and business interests of Japan’s nuclear industry helped create the safety oversights that led to Fukushima.

An observer can only hope that whoever does oversee Japan’s reconstruction — Kan for now — will seize the opportunity that this huge undertaking provides to root out some of Japan’s longstanding problems. Maybe in doing so, they might even fix that revolving door.

(Read “The Challenges Facing Japan’s PM.”)