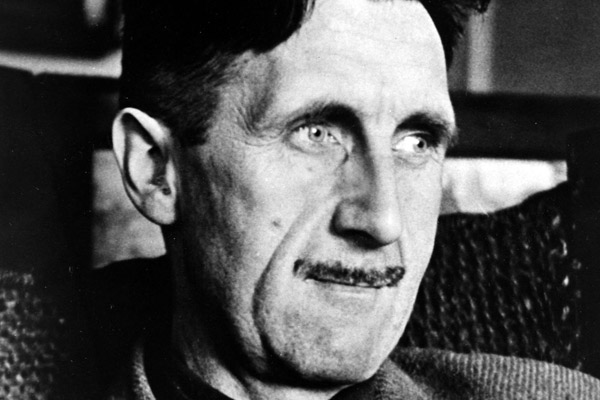

British author George Orwell (Photo: Popperfoto / Getty Images)

In the aftermath of World War II, George Orwell reflected on politics, power and language: “When the general atmosphere is bad,” he wrote, “language must suffer.” To wage war, to justify empire, the politicians of his time mashed words, turning English to euphemistic mush, he said. In turn, the “sheer cloudy vagueness” of political speech corrupted thought, anesthetizing our impulses. “When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims,” he wrote, “one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink.”

I thought of Orwell this week when I read Robert Gates’ remarks on Libya. “The way I like to put it is, from our standpoint at the Pentagon, we’re involved in a limited kinetic operation,” he told Fox. “If I’m in Gadhafi’s palace, I suspect I think I’m at war.” Right. Read it again. It’s not a war, it’s a limited kinetic operation. Unless you’re in the palace. Then, it’s war. I suspect. Hello, cuttlefish.

Let’s swim through the murk. To start: Where did ‘kinetic’ come from? In ordinary usage, ‘kinetic’ is an adjective used to describe motion. When ‘kinetic’ went to Washington, its secondary meaning — ‘active, as opposed to latent’ — came to the fore, explains Timothy Noah in a 2002 piece for Slate. The retronym ‘kinetic warfare’ started popping up a lot in the aftermath of 9/11, as Bob Woodward observed in Bush at War:

For many days the war cabinet had been dancing around the basic question: how long could they wait after September 11 before the U.S. started going “kinetic,” as they often termed it, against al Qaeda in a visible way? The public was patient, at least it seemed patient, but everyone wanted action. A full military action—air and boots—would be the essential demonstration of seriousness—to bin Laden, America, and the world.

Air and Boots. That’s the key. “The 21st-century military is exploring less violent and more high-tech means of warfare, such as messing electronically with the enemy’s communications equipment or wiping out its bank accounts,” Noah writes. But, “dropping bombs and shooting bullets—you know, killing people—is kinetic.” Appropriate, then, that the Obama administration is using it now.

Of course, it’s not just ‘kinetic,’ or Libya. Last year, Robert Fisk called attention to the way Pentagon-speak was seeping into the mainstream. Sending reinforcements is a “surge,” an increase in violence a “spike.” A surge, like a tsunami, or a tidal wave, erases what it hits. A spike, meanwhile, is temporary, measurable. Both are perfect examples of something Orwell abhorred: “strayed scientific words.”

By combining “limited,” “kinetic” and “operation,” Gates may have built the ultimate Orwellian euphemism. “Kinetic” connotes action, but the rest of it sounds vaguely, lullingly, scientific. It knocks you out then whispers—softly—sleep, sleep, forget about the war.