This is how we imagine royalty lives. On Sept. 12, at one of Scotland’s loveliest stately homes, the Prince of Wales and his 22 guests, more than a few of them stonkingly wealthy, have just finished dinner — risotto, sea bass and the stickiest of plum crumbles that generous belts of Puligny-Montrachet, Sarget de Gruaud Larose and pink Champagne only partially dislodge. Before the table rises, to be served digestifs and coffee amid a rare collection of Chippendale furniture under the gaze of long dead aristocratic beauties, there’s a musical interlude. A piper, in full ceremonial uniform — kilt, tunic, sporran, full plaid and a feather hat so tall its wearer dusts the doorframe as he enters — marches twice around the table, playing a medley of traditional Scottish music. One melody is easily recognizable: “The Skye Boat Song,” the story of Bonnie Prince Charlie, “the lad that’s born to be King.”

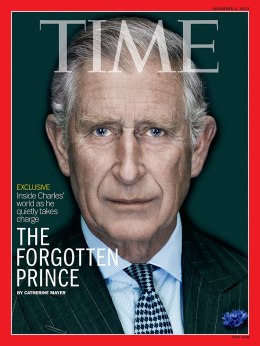

How I came to be a guest at that table — and to profile the modern-day Prince Charlie that’s born to be King for TIME’s latest cover story — is relevant to any understanding of the Queen’s eldest son and heir apparent. The picture that emerges in the cover story, through exclusive conversation and after extensive access to the Prince and his friends and associates, may startle. Much of what you think you know about the Prince is wrong. Much of what I thought I knew about the Prince was wrong. This applies both to the big picture and the small details. Who knew the secret of how he stays awake during speeches? Or what he’s like on the dance floor?

His Royal Highness Prince Charles Philip Arthur George, Prince of Wales, KG, KT, GCB, OM, AK, QSO, PC, ADC, Earl of Chester, Duke of Cornwall, Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick, Baron of Renfrew, Lord of the Isles and Prince and Great Steward of Scotland, might have led a dull, dutiful life of ribbon cutting and rite. Or he could have developed into a playboy or taken an interest in the arts or both. “There’s a long history of relationships between Princes of Wales and actors — not just actresses, not just the rude relationships as [Charles] would say, though God knows I’ve tried,” jokes the actress Emma Thompson, one of his close friends. “He wasn’t having any of it.”

(MORE: Behind the Cover: Prince Charles Like You’ve Never Seen Him Before)

Instead the Prince embarked on a quest. “I feel more than anything else it’s my duty to worry about everybody and their lives in this country, to try to find a way of improving things if I possibly can,” he said on Sept. 26, in conversation at another Scottish retreat, Birkhall on the Balmoral estate. Research for this piece took me to three of his official residences in England, Scotland and Wales, to Dumfries House, and trailing around with him to meetings and visits. I’ve discussed him in more than 50 interviews with his inner circle and his critics; plowed through biographies, his own writing and reams of articles and documentary footage. And I’ve thought about him. But then, I’ve been thinking about him for 28 years.

In 1985, the Prince invited himself to lunch at the newsweekly the Economist, where I then worked, to meet “people his own age” and discuss what he had already begun doing and might yet do to leverage his position to make the right sort of difference. I was far too junior to merit invitation to the lunch, but briefly chatted with the Prince and afterward heard accounts from those present. They were struck by the Prince’s earnestness, but it’s fair to say they were skeptical that he could understand enough of the real world to be effective. For much of his life, the Prince has struggled to convince the skeptics.

(Click here to join TIME for as little as $2.99 to read Catherine Mayer’s full cover story on Prince Charles.)

He’s easier to doubt. He’s a Windsor, a member of a family that has always seemed faintly comical, surrounded by funny folk who mistake pomp for pomposity. His mannerisms have proved a gift to impressionists; his turns of phrase a boon to satirists. Born with a megaphone in his hand, he may have stumbled into some debates without appreciating the backlash he could expect. But he has also united in unlikely alliance three strands of his opponents who have their own reasons for depicting him as a figure of derision: republicans, often of the left; traditionalists, often of the right and enraged by his radicalism on issues like climate change; and a smaller number who never forgave him for failing to cherish Diana, the late Princess of Wales, as they did.

In the decades after meeting him, I watched with interest as the gap between the person he had seemed to want to be and the petulant Prince of press reports widened. As those years passed and the green concerns he had espoused so early passed into mainstream thought, there seemed to be little acknowledgement of his role in promoting those ideas. His Prince’s Trust won plaudits for helping young people to find work or start businesses, but the Prince more rarely drew praise as a philanthropist. Eventually I approached his press handlers with a novel idea: they should let me inside the bubble to make my own assessment. To my surprise — and theirs — they agreed.

I found a man not, as caricatured, itching to ascend the throne, but impatient to get as much done as possible before, in the words of one member of his household, “the prison shades” close. The Queen, at 87, is scaling back her work, and the Prince is taking up the slack, to the potential detriment of his network of charities, initiatives and causes. “We’re busily wrecking the chances for future generations at a rapid rate of knots by not recognizing the damage we’re doing to the natural environment, bearing in mind that this is the only planet that we know has any life on it,” he said at Birkhall. Those future generations were well represented that day, as his son William, daughter-in-law Kate and their baby George paid him and his wife Camilla a visit. Isolated for much of his life, he now takes joy in his “wonderful wife. And of course now a grandson, which is what this is all about. It’s everybody else’s grandchildren I’ve been bothering about, but the trouble is if you take that long a view people don’t always know what you’re on about.”

The profile I’ve written I hope goes some way to explaining what the Prince is on about and serves up more than a few revelations about his life and his motivations. Because little in the Prince’s world is quite what it might appear from the outside.

The sumptuous dinner I attended at Dumfries House, for example: that wasn’t an occasion for the Prince to kick back and enjoy his unearned status.

Six years ago he heard that the 18th century mansion in Scotland was to be sold and its collection of Chippendale furniture dispersed. Sight unseen, he formed a consortium and bought building and contents for £45 million, about $72 million, part-financed by a £20 million, $32 million, loan taken out by his charitable foundation. As property prices declined globally, his critics suggested he had been as imprudent as the issuers of the subprime mortgages that triggered the slump, risking the financial health of his established charities on a self-indulgent whim.

But in securing Dumfries House, the Prince not only preserved a slice of heritage but also created in one of the most deprived corners of the U.K. a new hub for employment and for training courses run by his charities, and a potential magnet for tourism. His rich dinner guests are donors and potential donors, lured by his royal convening power to a place that needs their help and that would never have drawn their attention without Prince power. “When you get the Prince, you don’t just get him; you get all his charities as well. You get this huge force for good,” says Fiona Lees, since 2004 chief executive of East Ayrshire Council and keenly aware of the challenges to an area once buoyed by the mining industry. Its deep mines are shuttered and many opencast mines lie abandoned, filling with contaminated water. Local towns are leaching their populations; in New Cumnock, where the head count has fallen from 9,000 to 2,800, a staircase leads nowhere, the homes it once served torn down after they fell into dereliction. For communities without much hope, Dumfries House marks a rare investment.

As its 26 clocks strike 10 p.m., the Prince begins the task of extracting his sociable wife from a clutch of talkative guests. He’ll spend another two hours preparing for the next day’s early start and typically packed schedule of meetings, including one with Lees at which they brainstorm ways to stimulate the East Ayrshire economy and to deal with the blight of disused and dangerous mines. “We need people to help us think about this,” says Lees. The Prince promises to deliver. For most of his life, he has done so.

Click here to join TIME for as little as $2.99 to read Catherine Mayer’s full cover story on Prince Charles.