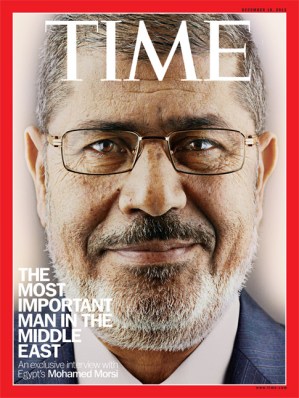

The most important man in the Middle East started 2012 as much a stranger to the people he now rules as he was to the rest of the world. Although Mohamed Morsi had long been part of the core leadership of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, he was viewed as a back-room operator, largely unnoticed among the Islamic party’s more charismatic political and religious figures. Not many outside of a handful of State Department Arabists in Washington had even heard his name.

And yet the year’s end finds Morsi instantly identifiable worldwide, even as his intentions in Egypt and the region remain very much unclear. In recent weeks, he has been hailed as a peacemaker by the U.S. and Israel, a savior by the Palestinians, a statesman by much of the Arab world—and branded a tyrant by the tens of thousands who have jammed Cairo’s iconic Tahrir Square since Nov. 22 to denounce him. Whether you think him a hero or a villain, the short, stocky Islamist with the professional air is navigating some of the world’s trickiest political waters.

(MORE: An Interview with Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi: ‘We’re Learning How to Be Free’)

Morsi doesn’t pretend his tenure has been perfect and argues it can’t be. Speaking with TIME in his first interview with the international media since the Gaza crisis, he points out that his government is Egypt’s first experience of real democracy. “So what do you expect. Things to go very smooth? No. It has to be rough, at least,” he says. But he also gives the impression of a man having a year to remember. “2012 is the best year for the Egyptians in their lives, in their history,” he says. “We’re suffering, but always a new birth is not easy, especially if it’s the birth of a nation.”

When the interview was scheduled, Morsi was riding high. His successful brokering of a cease-fire between Israel and Hamas had given him widening international and domestic support, a feat unmatched by any other Arab leader in the modern era, and offered the prospect that Egypt might again lead the region as it did under Gamal Abdel Nasser in the 1950s. Morsi had already displayed unexpectedly nimble political skills to pry executive power away from the Egyptian military. For a moment, there was even the possibility that Morsi had amassed just the right proportion of international credibility and domestic political capital to start delivering on the promise of the Arab Spring. But then he overreached. Instead of consolidating the power he had amassed in service of his country’s emerging democracy, he grabbed for more.

(MORE: Washington’s Two Opinions of Egypt’s Islamist President)

As Morsi spoke with TIME at the presidential palace in Cairo’s Heliopolis suburb, most of Egypt’s major cities were again ringing with the chant that had been the Arab Spring’s rallying cry: “The people want the fall of the regime.” The slogan that helped bring down Hosni Mubarak is now being hurled at the country’s first democratically elected civilian President by both cronies of Mubarak and the revolutionaries who toppled him. In Tahrir Square, judges appointed by the old dictator, many of whom enabled his decades-long repression of political dissent, joined their voices with liberal and secular activists. The most popular joke in Egypt these days is that Morsi has done the impossible: he has united the opposition.

Morsi achieved that by issuing an emergency decree on Nov. 22 appropriating for himself sweeping new powers, including immunity for his decisions from judicial challenge. The President insists his decree is a temporary measure designed to prevent politically motivated judges from undermining the process of creating a new constitution. But to critics, one particular provision, giving him “power to take all necessary measures” against threats to national security and to last year’s revolution, smells of dictatorship. Mohamed ElBaradei, the Nobel Peace laureate and liberal politician, dubbed Morsi the new pharaoh.

For the rest of the world, however, and especially the U.S., the stakes are even higher. Whether Morsi proves to be a reformer or an autocrat will play an outsize role in the prospects for continued peace with Israel, the fate of democracy in the Middle East and the balance of power in the world’s most unstable region. “We will soon learn what kind of leader he is,” says a White House official, “because this current episode is very much a test of his capacity to work effectively with all the various interests in Egypt.”

POLL: Should Mohamed Morsi Be TIME’s Person of the Year 2012?