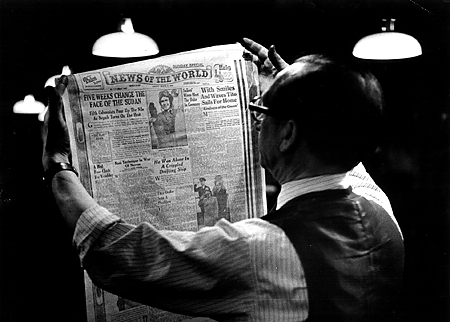

A printer studies a front page proof at the 'News of The World' office, 18th April 1953. (Photo: Bert Hardy - Picture Post - Getty Images)

UPDATE: Andy Coulson, former communications director for British Prime Minister David Cameron, is to be arrested Friday over his alleged involvement in the hacking of mobile phones while editor of the News of the World, according to the Guardian.

The end, when it came, was quick and brutal—not unlike the punchy stories about the no-longer-private lives of celebrities and politicians and ordinary people caught up in extraordinary events that became the hallmark of the News of the World’s coverage after Rupert Murdoch took over Britain’s biggest-selling newspaper in 1969. On July 7—six years to the day since suicide bombers created carnage in central London—Murdoch’s son James, the Deputy Chief Operating Officer of News Corporation and Chairman of its U.K. subsidiary News International, issued the Sunday tabloid’s death warrant. “The News of the World is in the business of holding others to account,” he said. “It failed when it came to itself.”

The July 10 edition will be its last. Mounting evidence of a criminal culture of phone hacking and paying police for evidence—alleged to have included the telephone numbers of relatives of the July 7 terror victims—had turned what was once a profitable asset into a liability, with advertisers canceling their campaigns and the contagion threatening to spread to other outposts of the Murdoch family empire, imperiling News Corp’s plans to buy all of the shares in satellite broadcaster BSkyB not already owned by the company. The implosion of the title was so rapid that News International’s public relations department sent out the text of its chairman’s statement without altering the standard paragraph that has garnished their news releases in the past:

News International Limited publishes the Times, the Sunday Times, the Sun and News of the World. In terms of growth, share, circulation and reader engagement, the company’s titles are among the world’s most successful.

Not any more, at least for one of those newspapers. A publication that lived for shocking banner headlines has become a shocking banner headline, with the loss of some 200 jobs and sacrifice of a circulation of 2.6 million, the first British national newspaper to close since 1995. But the story is far from over.

The next few days are likely to see more headline-making events. There are rumors of high-profile arrests: of journalists implicated in obtaining their stories by hacking into voicemails and of police officers suspected of being in their pay. The 11,000 pages of documents seized from private investigator Glenn Mulcaire, who has already served a prison sentence for hacking phones belonging to the British royals and their household and friends at the behest of the News of the World, could yield up more information about targets. After reports that mobile messages left for murdered 13-year-old Milly Dowler had been intercepted by Mulcaire, and in some cases deleted, the ex-con contacted the Guardian, the British broadsheet that has led the investigations into the News of the World far more effectively than Scotland Yard. He apologized for “anybody who was hurt or upset by what I have done,” and added this explanation:

Working for the News of the World was never easy. There was relentless pressure. There was a constant demand for results.

That culture may have been more extreme at the News of the World but the newspaper was not alone in pushing the boundaries of acceptable journalistic practice. The British press represents the best and worst in investigative journalism, unfazed by authority, determined to get to the truth, but liable to confuse the ideal of reporting in the public interest with reporting anything that might interest the public. That confusion is rife in the mass-market media but also contaminated broadsheet journalism as print titles have struggled for declining advertising revenues in the wake of the digital revolution. In 2005, a private investigator called Steve Whittamore was found guilty of extracting information from the police national database and giving it to newspapers. His client list included not only the News of the World but the tabloid Daily Mirror, mid-market Daily Mail and broadsheets including the Murdoch-owned Sunday Times and the Observer, the Guardian‘s sister paper.

It is not against the law to use a private investigator, and some of the stories resulting from such commissions would stand up to any public interest test. But much of the meat and drink of newspapers, as Mulcaire admitted in his Guardian apologia, is “simply tittle-tattle.” Amid a fierce competition for tittle-tattle, the News of the World will not be the only newspaper with guilty secrets. (Ironically, the more successful—and profitable—a title, the more likely it will have been able to invest in the dark arts.) The scandal that killed the News of the World should may yet spread to other news organizations. After David Cameron was attacked during his weekly question-and-answer session in the House of Commons on July 6 about his failure in judgment in hiring an ex-News of the World editor as his communications director, the Prime Minister’s advisers huddled with parliamentary journalists to discuss the debate and the unfolding controversy. A journalist from the News of the World‘s sister paper the Sun was eager to hear about Cameron’s plans for one or more public inquiries into the scandal. “Can you confirm any inquiry will look into all news organizations?” he asked, anxiously.

The answer, as that journalist was assured, is that any inquiry should investigate malpractice wherever it may have occurred. That must include the extraordinarily poor performance of the police in failing to investigate properly while, if allegations prove true, some of its own officers lined their pockets by helping the News of the World to break the law. But here’s some news the Sun won’t give prominence: the closure of the News of the World may not be enough to draw fire from News International. Rebekah Brooks, its chief executive, remains in her post although the reported hacking of Milly Dowler’s mobile would have happened on her watch as News of the World editor. And the MP Tom Watson used parliamentary privilege to raise questions about James Murdoch’s probity, suggesting he had been involved in a cover-up. Moreover rumors envisage a ghostly afterlife for the News of the World, if the Sun, currently published Monday through Saturday, should become a seven-day operation.

So the controversy is set to continue, with lashings of high drama, twists and turns and celebrity appearances. It’s just the sort of stuff that sells newspapers.

Catherine Mayer is London Bureau Chief at TIME. Find her on Twitter at @Catherine_Mayer or on Facebook at Facebook/Amortality-the-Pleasures-and-Perils-of-Living-Agelessly . You can also continue the discussion on TIME’s Facebook page and on Twitter at @TIME.